Ciao,

how are you?

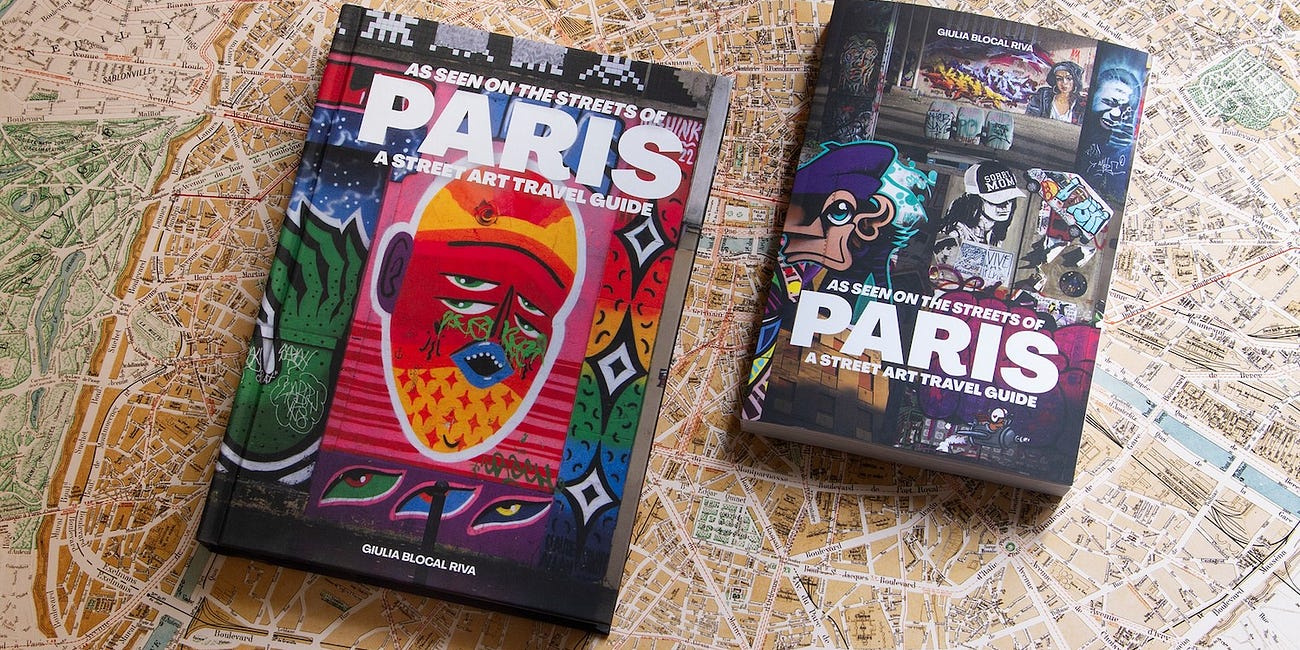

There’s no other way to begin this monthly letter than by thanking you for all the kind messages you sent after the special edition of the newsletter announcing the pre-order of my independent, self-published book As Seen on the Streets of Paris. 🥰

Your words truly warmed my heart and gave me the motivation I needed to push through the final stretch of this challenging journey (who knew self-publishing could be so tough!).

That final stretch? Distribution—also known as my latest lesson in how reality works.

I structured my whole communication around “buy it at local bookshops” because, in the true “Be Local” ethos, I genuinely wanted to support small, independent bookstores everywhere. It felt like the perfect match: a self-published, DIY book sold through independent shops. It turns out, though, independent bookshops aren’t too eager to support independent authors, they prefer sticking with publishers.

I can’t say it isn’t disappointing. I had this idealistic vision of independent bookshops rallying behind independent authors, but that’s clearly not how things work. And having championed independent bookstores for years—always going out of my way (literally!) to shop local and regularly featuring them on my blog, which, on top of everything, is called Be Local (ironic, isn’t it?)—it feels like a personal betrayal. Almost as if the very world I’ve been supporting all along has turned its back on me.

Anyway, pre-orders are doing well on Amazon (oh, the irony!), especially for readers in the USA and UK, who are getting the best deals. And I’ve just adjusted the wholesale discount to help bring the final price down in Europe, where things are a bit more complicated because each country has its own pricing structure. (Pricing is another lesson I’m tackling now—figuring out the right numbers and percentages to make everything work, because beyond a certain point in the distribution chain, the pricing is no longer in my control.)

I’m sharing all this because I feel like you’re in this with me—you’re part of the BLocal journey. Some of you were even there with me in Paris when we took the photos for the book. Moreover, in the emails you sent after the book launch, a few of you expressed curiosity about the self-publishing process, so I thought I’d share some insights. After all, this newsletter has always been a way to give you a glimpse behind the scenes of BLocal. Let me know if there’s more you’d like to hear!

Until next month—until next year, actually…OMG, it’s 2025 already!

Giulia

The heart of street art still beats strong 💓

I began outlining this editorial before my trip to Athens, initially planning to focus on the 'new' Nuart festival. At the time, I was captivated by the idea that, in some corners of Norway, street art still thrives as a grassroots movement—a reclaiming of urban spaces from commercialization and institutional control.

Enthralled by Martyn Reed's pivot toward the roots of street art as unsanctioned expression and community-driven activism, I even published an interview we conducted over a year ago at Nuart Aberdeen 2023—an interview I had been procrastinating on ever since.

But last night, as I was scrolling through my phone, I stumbled upon something far more shocking—so striking that it must become the starting point for this reflection on the state of art in the streets.

During Miami Art Week—which, alongside several high-profile art fairs, hosts Wynwood Walls, the world’s most celebrated street art event—someone decided it would be a good idea to rent out vertical surfaces in public spaces for artists to display their work. Essentially, they’re selling street space to artists, asking them to pay to showcase their art in the urban public space.

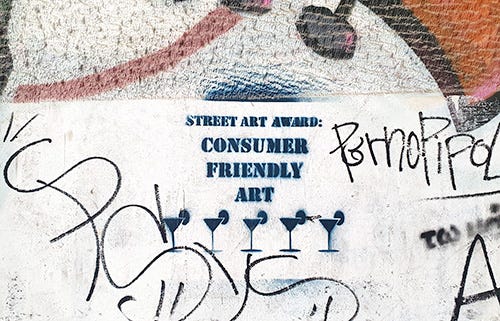

If you consider that street art—as in "art in the streets"—was partly born as a reaction against the advertising saturating public spaces, it’s clear we’ve come full circle in the most ironic way possible.

From activism to advertising: the commercialization of urban public spaces.

When I began drafting this editorial two months ago, my focus was on how street art has increasingly been co-opted by institutions, often turning it into a sanitized tool for urban renewal and gentrification.

I was reflecting on branded murals and street art festivals that prioritize the interests of real estate developers over those of the local community—topics we’ve already explored several times in this newsletter.

In one word, the Disneyfication of street art culture: when festivals prioritize large-scale, sanitized murals designed to appeal to tourists and commercial interests, they strip away the raw, edgy character of street art, reducing it to mere entertainment devoid of its original activist and rebellious spirit.

In As Seen on the Streets of Paris, I discuss the example of the 13th Arrondissement, where the popular project Boulevard Paris 13 brought massive murals to the blank walls of buildings in the district's eastern part. However, the selection of mural locations is not made by the artists themselves but carefully planned by curators and administrators, who strategically choose walls to create curated urban art trails. The downside of such projects is the transformation of street art from its original, unsanctioned form into a highly organized and controlled endeavor.

This trend is evident in “street art districts” worldwide, from Berlin’s Kreuzberg to New York’s Bushwick, where the art form has been repurposed as a tool for urban redevelopment, losing its authentic, spontaneous connection to its context.

While sometimes driven by municipalities, the worst cases involve real estate developers, as seen with Miami’s Wynwood Walls. Long before introducing the concept of artists renting street space, the city of Miami had already exemplified how developers use street art murals to drive up property values, leveraging art to fuel gentrification.

But let’s save the gentrification debate for another editorial. For now, let’s carry on with some positive examples of good practice.

Not everything has been corrupted or lost!

There are still festivals that champion creativity beyond traditional boundaries, fostering spontaneous, unplanned art in spaces that are neither pre-designated nor heavily curated.

Nuart Festival exemplifies this ethos, particularly with its "new" format that embraces unsanctioned street art, allowing artists to reclaim public spaces on their own terms. Similarly, festivals like Stencibility in Tartu—where I took you last summer—provide platforms for artists to create freely, preserving the raw, rebellious spirit that lies at the heart of street art culture.

I believe that what we should truly hope to see more often in the streets is human-scale street art—a return to the origins of the movement. As Martyn Reed put it in our interview:

“What’s the point of a big mural? It’s too in-your-face. You’re not discovering it anymore; you’re not just stumbling upon it. Those human-scale pieces feel so much more… human. They spark different reactions. Anything bigger than you has power over you—like a massive McDonald’s sign or a towering building. These things aren’t neutral; they make you feel small. The bigger the billboard, the smaller you feel.”

Human-scale works not only connect more deeply with their surroundings but are also crucial to preserving the independence of street art culture. They can be created without cherry pickers, scaffolding, or the logistical machinery that demands significant financial investment. This independence matters. It means artists don’t have to rely on external funding or compromise their vision to meet someone else’s expectations. Human-scale works are the heart of a culture that thrives on autonomy, spontaneity, and an unfiltered connection to the streets.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on these topics—feel free to reply to this newsletter and let’s keep the conversation going!

And if you’re at Miami’s Wynwood Walls right now, or if you’ve visited in the past, I’d love to hear your impressions. I’ve always wondered why so many artists I admire and respect, from Martha Cooper to 1UP Crew, have acted as the event’s ambassadors. I feel like I must be missing something—the reason why so many people attend so enthusiastically. So please, enlighten me! (I’m not being sarcastic; I genuinely wonder and would love to know.)

You can share your thoughts directly with me by replying to this email or with the BLocal community in the comments section on Substack.

New on the blog!

Martyn Reed’s Round-Trip Journey to the Origins of Street Art Festivals.

Martyn Reed, a pioneering curator in the street art world, founded Nuart Festival—the first-ever street art festival—in Stavanger, Norway, in 2001. Through Nuart, he has been a driving force in reclaiming public space and making art accessible outside traditional gallery settings.

This fall, Nuart Festival returned to Stavanger after a multi-year hiatus, adopting a “back to basics” approach that reasserts street art as a medium for exploring and redefining public spaces.

Top Places to Discover Amazing Street Art Across France.

After publishing my book As Seen on the Streets of Paris, which delves into the diverse street art of the city, I’m now expanding my focus to explore the best places across France where street art thrives.

From towering murals in Grenoble to the colorful alleys of Marseille, this guide highlights the top street art destinations in France.

👇 The most clicked link last month 👇

I rely on the support of readers like you to keep creating genuine and informative content. If you value my work and would like to see more of it, please consider making a donation to support my writing and my editorial project BLocal.

You can Buy me Pizzas or Donate via Paypal.

If you are currently unable to make a donation but find this newsletter and my street art travel guides in general interesting, you can help grow this community by forwarding this email to anyone you like, or sharing this post on your social channels.

I was under the impression that Wynwood Walls commissions—not charges—artists to create large-scale murals there. And it's not an event; it's essentially an open-air museum that's open year-round. Are you sure that the advertisement you posted a screenshot of is for Wynwood Walls? Looks like it might be something different, as Wynwood Walls is in Miami proper, not Miami Beach.

The question could be if there's only one type of "authentic street art"? I mean what you want to say in the article, but street art is always progresses and changes as all types of art do. If that is true, are the "flowers colourfuls walls" in a touristic place st.art? I don't know, but you know the artists needs more things than expressing themselves freely.