📤 I sent an email to Banksy.

A book signing, a street art trip, and the next book taking shape.

👋 Ciao, I'm Giulia Blocal, your street art insider. This is Beyond the Walls, a monthly deep dive into street art, graffiti, off-the-beaten-path travel, and a bit of my life in between.

This month, I’m picking up where we left off in February, expanding the reflection on intellectual property and street art. Since then, I’ve been in touch with over 300 street artists to request permission to include images of their work in my upcoming London street art book. This process sparked quite a few reflections—especially when it came to artists like Banksy, who stands alone in trademarking his street art instead of relying on copyright. Also adding fuel to the fire: a recent controversy in Italy, where a wine fair used Keith Haring’s drawings without permission, sparking quite the debate.

But first, a few updates on my life and the BLocal project.

Let’s jump in!

Ciao,

how are you?

This month, I’m writing from Paris (or more precisely, from Pantin), where I spent two weeks eating French cheese and exploring the city together with some of you (🫶) through five carefully designed urban walks.

We had such a great time exploring Paris’s street art together—roaming far and wide under an unusually sunny sky. But more than the art itself, what made these walks truly special to me was the chance to connect with you in person. As someone who spends a lot of time writing behind a screen, nothing compares to the joy of stepping out into the streets and sharing this passion face to face.

These moments of real-life connection mean a lot to me—walking side by side, looking closely at walls, and digging into the stories behind each artwork. Who is the artist? How do they work? Why this wall, this image, this moment? Together, we explored how each piece is rooted in its surroundings—how it reflects, challenges, or quietly responds to what’s happening in the neighborhood around it.

Street art doesn’t just speak to the city; it speaks with it, echoing local histories, addressing social tensions, or simply asserting a presence in an ever-changing urban landscape.

Whether it’s a poetic intervention tucked in a quiet alley or a massive mural overlooking a busy boulevard, each piece tells a story—not only of the artist but of the neighborhood too.

I love helping you connect the dots—between different works, between past and present, between an image and the history of the area it inhabits. And during these walks, I could see those connections clicking into place for many of you, which was honestly the best part.

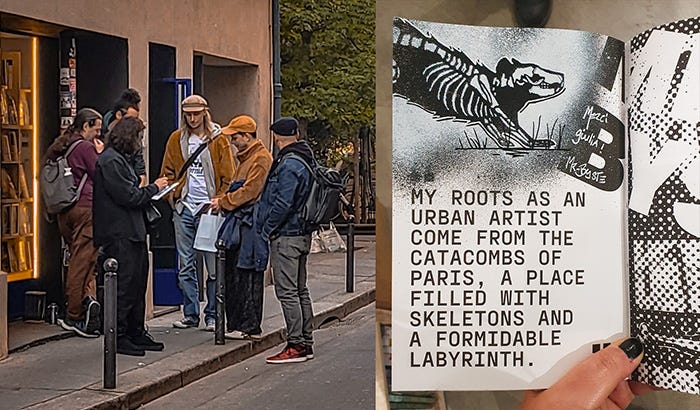

A real highlight of the trip came at the end of our first walking tour: we wrapped up the day at

—the coolest bookshop in town—for the signing of my Paris Street Art Book.Surrounded by friends, artists, readers, and curious passersby, it was a heartwarming celebration of everything I love most about this work: sharing stories, exchanging ideas, and turning a solitary passion into a shared experience.

Before heading to Paris, I spent three intense weeks reaching out to every single artist featured in the London book — nearly 300 of them — to ask for permission to use images of their work. A massive undertaking, but a necessary one.

This time, I was way more organized: two spreadsheets, three folders, and a system to keep track of every confirmation I received. A far cry from the chaotic process I followed for the Paris book, where I’d squeeze in a couple of hours a day for three months and let all the confirmation emails get lost in the sea of everything else I was juggling (proofreading, designing collages, setting up the automated email sequences linked to the map’s QR code…).

Reaching out to artists — especially the ones who never reply — is honestly the part of my job I dread the most. There's a very specific kind of anxiety that hits every time I have to send another "Ciao, just following up..." message across email, Instagram, WhatsApp. After a few rounds of this, I can feel the migraine brewing. It’s like clockwork.

But this time, I chose to face it head-on. For three weeks, this was all I did. No distractions. No excuses. Just me, the spreadsheets, and the silence of unread DMs.

It was exhausting, but it also made me revisit some thoughts we didn’t get to cover in the February 1st newsletter — the one about street art and intellectual property. So I’ve dedicated this month’s essay to dig a little deeper into those reflections.

You’ll find it just below.

Happy reading — and who knows, maybe I’ll see you in Lisbon before next month’s issue 😉

Giulia

P.S. Before the trip, the book signing, or even the Urban Art Fair (which I review below, after the Banksy essay), I hit the streets of Paris on a paste-up mission with the Murmure street art duo—and shared a reel about it on Instagram. Check it out!

✈️ Travel with me!

There are still a couple of spots available for the Lisbon street art trip, taking place from May 8th to 12th, check the program out!

From Walls to Wall-ets: The Business of Street Art Reproduction.

Exactly three months ago, we were talking about Ernest Zacharevich and the unauthorized commercial use of his artwork in Malaysia. Now, a similar story has unfolded in Italy—just ahead of Vinitaly, the country’s leading wine fair. For its opening event, the organizers launched a full-scale visual campaign built around reworked images of Keith Haring’s art—without ever obtaining permission.

The Keith Haring Foundation, which manages the rights to the artist’s work (and channels licensing revenue into nonprofits supporting children and AIDS-related causes—the disease that claimed Haring’s life), quickly clarified that no authorization had been granted.

To make matters worse, the campaign didn’t even credit Keith Haring.

As I wrote in the February 1st newsletter: “The right of attribution is paramount.” So not only did the organizers fail to ask—they also failed to acknowledge. Forget paying for a license—they didn’t even put the artist’s name on it.

Is Copyright for Losers? Reproducing Banksy’s Artworks.

I’ve already written about the paradox of law enforcement stepping in to protect illegal art—first when Banksy’s London Zoo series unfolded before my eyes, and later after watching the documentary Banksy and the Stolen Girl. So rather than revisiting those reflections, this time I want to focus on what happens when a work of street art is reproduced—whether for unauthorised merchandise or in any other context where third parties profit from it (as in the above-mentioned cases of Keith Haring and Ernest Zacharevich).

Copyright, in its traditional form, requires an identifiable author—someone who can be named, credited, and, if necessary, summoned to court. But Banksy has built his entire persona around anonymity, operating outside institutional systems and legal frameworks. As a result, claiming copyright becomes complicated—if not impossible.

Instead, Banksy turned to trademarks. By registering his name and certain images as trademarks, he found a legal workaround that allows him to block unauthorised commercial use—without compromising his identity.

The cornerstone of this strategy is Pest Control, the official body that authenticates Banksy’s works and manages legal matters on his behalf. It exists to preserve the integrity of his art while shielding him from commercial exploitation.

Despite these efforts, Banksy’s imagery has been widely—and often shamelessly—appropriated. From canvas reproductions to greeting cards, mugs, t-shirts, and even entire exhibitions, his work has been co-opted repeatedly without his consent.

One of the most prominent players in this grey market is Full Colour Black, a UK-based greeting card company that has been using Banksy’s images for years. The ongoing legal battle between the two has become emblematic of the limits and loopholes in Banksy's legal protections. Full Colour Black claims that Banksy doesn’t make genuine commercial use of his trademarks and therefore shouldn't be entitled to hold them. Banksy, on the other hand, accuses the company of exploiting his work under the guise of homage.

To counterattack, Banksy did something brilliant: he opened a shop. In 2019, Gross Domestic Product launched as a pop-up in Croydon, London, offering officially sanctioned merchandise—clocks, mugs, welcome mats, and more:

The shop was both a legal manoeuvre and a conceptual artwork—a tongue-in-cheek way to satisfy trademark requirements that demand a product be “used in commerce,” all while satirising the very idea of selling out.

Can Street Art Be Protected Without Being Institutionalised?

Back in 2005, in his book Wall and Piece, Banksy boldly declared, “Copyright is for losers.” The line summed up his anti-establishment ethos and his disdain for the commercial structures of the art world.

Yet today, in order to shield his work from unauthorised exploitation, he’s forced to engage with those very systems—registering trademarks, issuing legal threats, and navigating the bureaucracies he once mocked.

In the end, even Banksy can’t escape the machinery he critiques. The moment street art becomes valuable, it becomes vulnerable—and protecting it means making compromises that blur the line between rebellion and bureaucracy.

I Have a Confession to Make…

I’ll end with a personal note.

I have three unauthorised Keith Haring tattoos.

I never asked the Keith Haring Foundation for permission—although I did once send them photos of the tattoos as an attachment to a cover letter when I applied for an internship there. (No wonder they never replied.)

But if they had, and those tattoos had shown while I worked there, I’d probably have borrowed Banksy’s words: “It’s always easier to get forgiveness than permission.”

✍️ New on the Blog!

Discover the Unexpected Street Art in Versailles.

When you hear “Versailles,” chances are your mind jumps straight to the lavish palace, ornate gardens, and golden gates. But just beyond the royal façade lies a different kind of artistic treasure—one that’s painted on walls.

Welcome to the street art scene of Versailles, where murals tell stories that are far more contemporary than classical, and creativity thrives far from the tourist path.

Urban Art Fair Paris 2025: A Day at the Vernissage.

Now in its 9th edition, Urban Art Fair Paris brings together a rich mix of contemporary urban art, from solo shows to collaborative projects and immersive installations.

During the vernissage, the exclusive preview for press and VIPs, I had the chance to explore the eclectic displays, connect with artists, and experience the unique atmosphere that defines the fair.

🔁 Updated

Exploring Pantin, the Brooklyn of Paris.

This time, I didn’t just explore Pantin—I made it my base, my home for ten days. Staying here allowed me to truly soak in the local atmosphere and I can now say with certainty that this is my favorite corner of Paris: genuine, alternative, down-to-earth, and surprisingly green. It couldn’t be further from the usual Parisian clichés!

I rely on the support of readers like you to keep creating genuine and informative content. If you value my work and would like to see more of it, please consider making a donation to support my writing and my editorial project BLocal.

You can Buy me Pizzas, Donate via Paypal, or become a Paid Subscriber.

You can also buy my book, As Seen on the Street of Paris, “like” my newsletters by tapping the ❤️, share them on Substack Notes or other social media, and forward this email to anyone you like.

Last year I went to exhibition in Tallinn, Estonia, dedicated to Banksy art. It felt nice to buy a mug an postcard with his art. I knew that it's not original, but I wanted to have something that reminds me of that exhibition. I liked it! It was informative, interactive and very interesting. But after reading your blog now I'm concerned if this was right. I just haven't been in Bristol or London yet.